In 1896 at the Chicago Coliseum, an American football game was played indoors for the first time. The University of Chicago beat Michigan by the slimmest of margins, 7–6. While one writer declared “the idea of football indoors must have been pronounced a failure.” Evidently he lacked the imagination to see the possibilities. His colleague at the Delphos Daily Heraldextolled:

“One thing at least was settled by the game, and that is, that indoor football is literally and figuratively speaking a howling success. The men had no trouble in catching punts, and football was played on its merits, without the handicaps of a wet field or a strong wind. Toward the end of the second half it got very dark, and the spectators were treated to a novelty in the shape of football by electric light.”

And at the Nebraska State Journal:

“Indoor football is an innovation, but it promises to become a permanency for late games. While the other fields about Chicago were sloppy and the players were floundering about in the seas of mud, the athletes in the Coliseum played on dry surface and secure from the elements. A two-inch layer of tan bark was placed over the hard earth, and there was no inconvenience from dust. None of the punts touched the beams overhead and spectators and players were captivated with the comfortable conditions under which the game was played. Darkness came on at 4:00 and the players were scarcely distinguishable for a time, but electric lights soon rendered each play distinct.”

Indoor Football is an Innovation

Imagine if one of these men walked into the Dallas Cowboys Stadium today.

So it is somewhat surprising that more than 50 years later, baseball was still subjected to the elements. It simply was not yet possible to fit a baseball field in even the largest indoor spaces of the time — but everything was about to change.

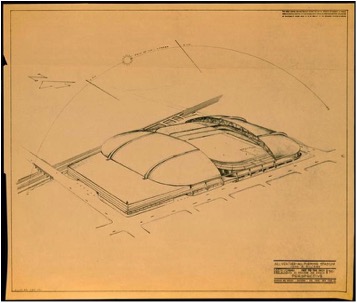

The concept was first floated as part of Walter O’Malley’s efforts to build a new home for the Dodgers to replace the aged Ebbets Field. Norman Bel Geddes, an architect and designer of acclaim and a pioneer who envisioned the future of sports. As reported in James Gast’s excellent book: The AstroDome: Building an American Spectacle, when the drawings were publicly shared in 1952, a new concept for stadiums had a emerged, one we are all very familiar with today.

“The sketches showed a sleek structure that contained not just a ballpark but also a full-fledged shopping center complete with supermarket, service stations, playgrounds and a movie theatre, all above a 5,000-car parking garage… Inside the ballpark itself, Bel Geddes proposed heated foam-rubber seats, each equipped with an automatic hot dog vending machine (mustard included).”

Norman Bel Geddes & Company perspective drawing of an all weather stadium for the Brooklyn Dodgers, 1949. (The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center. (c) The Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Foundation, Inc.)

While no one may know exactly what transpired in the mid-50s in New York that prevented the new Brooklyn Dodgers stadium to be built at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues but following 1957 season, O’Malley pulled the trigger and indoor baseball would have to wait for another decade to turn over before it would get its chance.

In 1960, Seth Morris was summoned to a meeting. Although limited in their experience developing athletic facilities and barely more with large-scale projects, but relationships and a career as a second-string infielder for his high school baseball team, Morris’s firm secured the contract along with another local Houston firm, Lloyd and Morgan (my soccer readers just got a chuckle) — who in 1950 had completed Rice Stadium (incidentally another recent AstroTurf project).

But Rice’s storied stadium history is for another day. This is a story about the AstroDome.

That meeting one of the principals, the Mayor of Houston, Judge Roy Hofheinz declared that Houstonians could not be expected to attend ball games in the hot sun and high humidity of the Texas summer, especially with significant mosquitos as a result of the humidity. He went on to say it had been decided that the new stadium in Houston would be large enough for 65,000 people, fully enclosed with a dome, be air conditioned and would have natural grass.

Easy. Morris hastily responded to the challenge: “Hell, we’ll do it!”

He could not have possibly known what he and his colleagues were getting themselves into. But the decision had been made, a dome was going to be built and the team was assembled to design it.

“Well, it was scary. But we weren’t doing anything really new. Everything we did had been done before; it just hadn’t been done to that scale.” — S.I. Morris

The ideas that came next were wild. Gast fills this and many of the other gaps that I’m leaving out in the book but one that warrants mentioning was a design-build proposal “from Oregon-based Timber Structures, Inc. which proposed to build the enormous dome out of structural timber. The company produced a drawing showing its approach…the huge roof would have been framed with laminated timber trusses, with members 11 inches wide by 42 inches deep, fastening together with huge steel gusset plates the size of tabletops.”

A lamella roof, a German invention dating from 1908, utilizes the structural principle of triangulation comprised of a number of intersecting steel beams forming a diamond-shaped pattern.

At the groundbreaking for the “Domed Stadium”.

It was happening and happening fast in Texas. Texas was at the center of the world’s attention, an while Dallas has a distinct somber association in the 60s, it was Houston, home to NASA and the oil money where everything seemed possible. Hell, at the groundbreaking for the “Domed Stadium” as it was known at the time, the dignitaries shot Colt 45s into the ground. This seems less effective than shovels but amasses maximum Texas credibility.

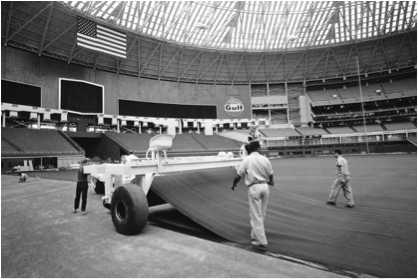

While others were worried about air conditioning and luxury features, Ralph Anderson, Jr. was dealing with something more important entirely, how does one grow grass indoors.

Large skylights would reduce the area available for acoustic absorption and would increase the impact of the sun, asking more for the massive air conditioning system. Gast captures the conundrum poetically “a case of clashing priorities on a grand scale.”

“Anderson tried to find a way around this technical challenge by using artificial grass. The problem was, at that time, such a product did not exist. During the winter of 1960–61, he canvassed manufacturers of synthetics: Union Carbide, 3M, Dow Chemicals, U.S. Rubber and Dupont. Anderson also reached out to carpet manufacturers. While a few of the companies reported they were tinkering with ideas for artificial turf, non had a suitable product ready for market.”

The architects attempted to invent synthetic turf, going as far as creating drawings but could not find a suitable manufacturing partner. Gast reports that was for the best, quoting a Hofheinz aide, Tal Smith:

“If Hofheinz or the architects or anybod else had gone and said… ‘we’re not only going to have a roof and air conditioning but we’re not going to be able to play on grass’ … no way that would have ever been accomplished…you had to grow grass.”

So while all efforts went into selecting the best grass and pushing the limits for what grass could take, Hofheinz may not have been disappointed to hear the sub-optimal results.

The Judge may even have quietly welcomed the news. In fact, Hofheinz had been talking about artificial grass for years, probably thinking of his need to rent the Dome for conventions and trade shows. Sunlight aside, there were lots of good reasons not to plant real grass in the new Domed Stadium. An artificial surface would greatly simplify the process of converting the stadium from baseball to football. For a convention or trade show, real grass would need to be cut into squares, removed from the field, and stored in a location where it could be kept damp. It would be a constant headache…

Hofheinz had mentioned synthetic grass in the press as early as 1963, referring to it as “undertaker’s grass” after the plastic covering used by funeral directors to discreetly conceal soil piled at gravesites.

By 1964, Hofheinz was saying publicly they intended to do away with the natural grass — they simply could not have anticipated how soon that would be.

Houston Colt .45s (1962–1964) left was abandoned in favor of the Houston Astros first logo (1965–1976) on the right.

In December of 1964, Hofheinz announced that the Colt .45s would rebrand as the Astros — the Colt Firearm Company still owned the trademark and was expecting to share in merchandising revenue. A few days later, he held a press conference that Harris County Domed Stadium would be called The AstroDome.

AstroDome — the 8th Wonder of the World

Following the dome’s completion the players took the field and reported that the infield grass was “neither too slow slow nor too fast.” But the outfield was a different story.

“Several players were having some trouble tracking fly balls. The 4,596 Lucite skylights had been designed to diffuse bright sunlight, and they did that job well — too well, as it turned out. Rather than limit the painful glare of direct sunlight to a single orb in the sky, the diffusing layer of the skylights spread it over a much larger area. Players stumbled around, assuming a defensive posture when a ball headed for the roof and then missing it completely when it fell to earth.”

“It was like looking at a million suns. You just couldn’t see a thing. — Astros Shortstop Bob Lillis

Astros players began wearing batting helmets into the field during day games.

“If it’s a cloud day, you got a 50–50 chance of catching the ball. When it’s sunny and you get that glare, there ain’t no way you can catch a ball.” — Astros Outfielder Jimmy Wynn

Thousands of letters piled in from individuals and companies suggesting everything from tethering blimps during day games to create “a man-made eclipse” to polarized sunglasses for players. May 23rd the decision was made, paint the skylights out.

As expected, the grass began to die. But the rest of the world was paying attention and domes were considered for Shea Stadium, RFK, even Boston looked at a new domed stadium they would have abandoned Fenway for.

People started buying tickets to every event the building hosted, from selling out a Boy Scouts Circus and even the Astrodomes’s Skipper’s Jamboree and Preview (boat show) drew unmistakable crows that could only be there to see the AstroDome in its glory.

Astroturf is Born

Tal Smith was the man that Hofheinz tasked with replacing the dead grass: “Tal, I don’t care what you have to do — find a solution to this. You’ve got whatever you need.”

“His office soon filled up with samples of carpet, rubber flooring, paints and lawn chemical products, but after a few weeks Tal had seen ‘nothing that warranted a second look.’”

Initially the product was called “Chemgrass.”

Then a call came that changed sports forever. Dick Theibert, Athletic Director at Brown University invited Smith to Providence to see a new artificial turf product that had been installed at Moses Brown School a few blocks from Brown.

While AstroTurf has since taken on a cultural significance and was ever-present in the 60s and 70s from front door mats to the Brady Bunch’s yard but before any of that could happen, Smith had to fly to Providence and see for himself.

“It felt good, it looked good and the ball seemed to react alright.” — Tal Smith on his first impressions of “Chemgrass” in Rhode Island.

The nylon turf had a distinct color that was seen as a bonus described in Gast’s book “as pure a green as you’ll find on the most beautiful golf course in the world.” It complimented the rainbow seats in the Dome nicely. But you shouldn’t assume green was the only choice. A more bold scheme would have seen blue in the infield, yellow in the outfield and red along the foul lines.

So 50 Years Ago Today, April 18, 1965 at Around This Hour, Astroturf Entered the World of Sports.

Between innings “earthmen” made a show of vacuuming the turf… but their vacuums were not connected to power.

The field (as we all now know) was fast — very fast — but the Astros who had been saved from bad hops and divots from the dead grass of the previous year adjusted, changed their footwear and learned to account for high bounces and a movement had begun.

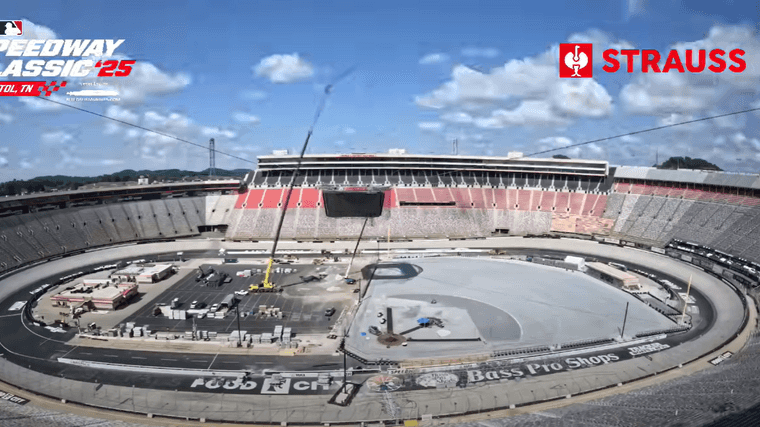

Other teams raced to catch up and by 1971 seven major league parks had the space age surface.

The AstroDome

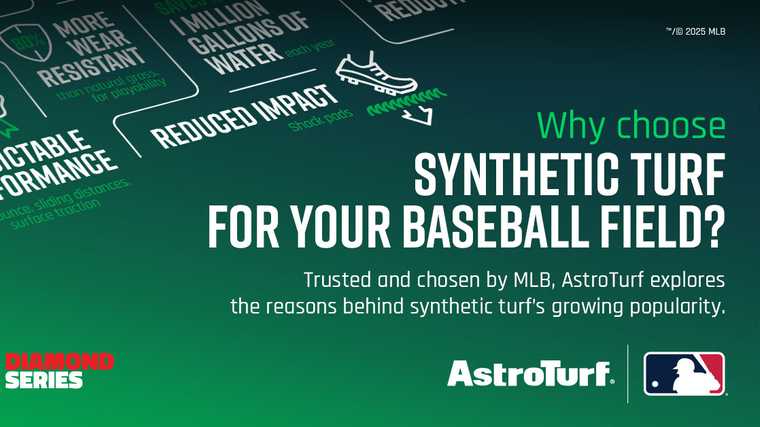

Today, AstroTurf continues to lead the industry into the future with its commitment to safer, more durable and cooler fields. It is truly hard to imagine American sports without the vision and execution of the AstroDome and the successful entrance into the professional field building business for AstroTurf.

The AstroDome still stands but is no longer looked after the way it once was with the addition of NRG Stadium, home to the Texans to the AstroDome’s original footprint.

More great photos are available through this Columbia University website.

Much of the information contained within this article is from the incredibly well researched book on the topic: The AstroDome: Building an American Spectacle